Description

One of the better condition and RARE excavated artillery bolts (solid, not hollow) from the famed Whitworth cannon, one of the most accurate artillery pieces of the entire Civil War era. The Whitworth, designed by Joseph Whitworth and manufactured in England, was not only a rare gun during the war but was an interesting precursor to modern artillery in that it was loaded from the breech and had exceptional accuracy over great distance. An engineering magazine wrote in 1864 that, “At 1600 yards [1500 m] the Whitworth gun fired 10 shots with a lateral deviation of only 5 inches.” This degree of accuracy made it effective in counter-battery fire, used almost as the equivalent of a sharpshooter’s rifle and also for firing over bodies of water. It was not popular as an anti-infantry weapon. It had a caliber of 2.75 inches (70 mm) although commonly called a 3″ rifled gun or 10 pound rifled cannon. The bore was hexagonal in cross-section and the projectile was a long bolt that twisted to conform to the rifling. It is said that the bolts made a very distinctive eerie sound when fired which could be distinguished from other projectiles.

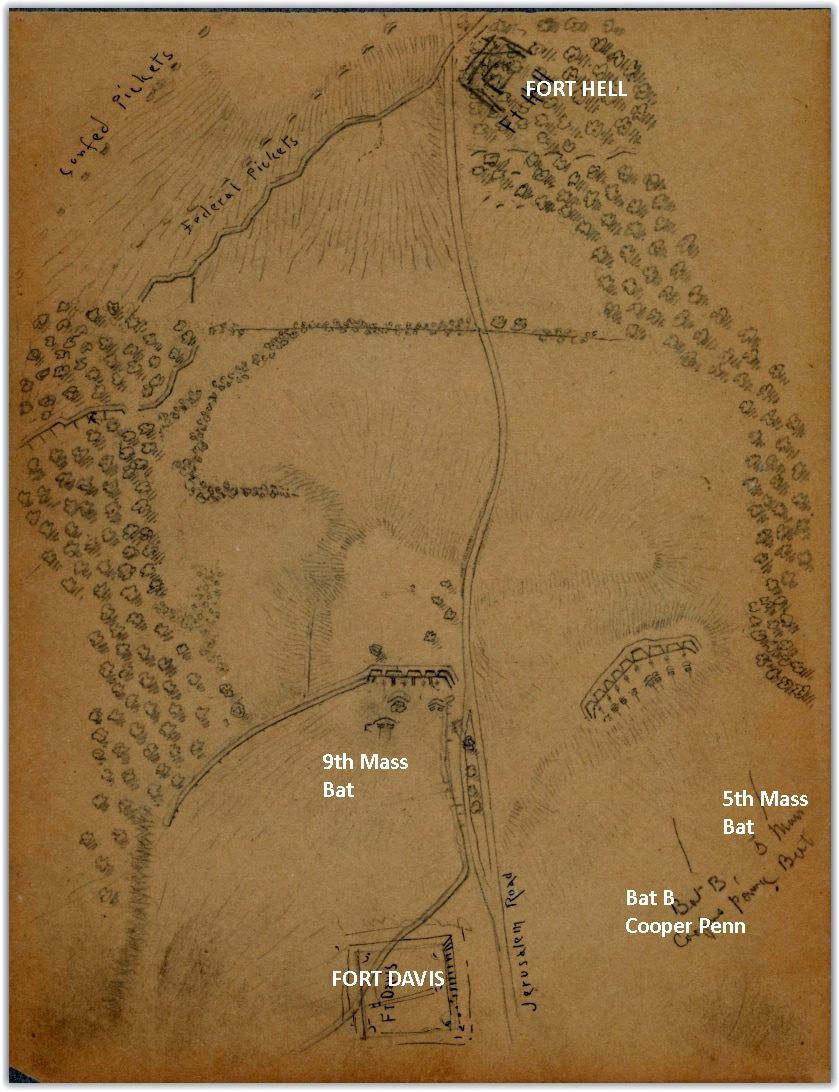

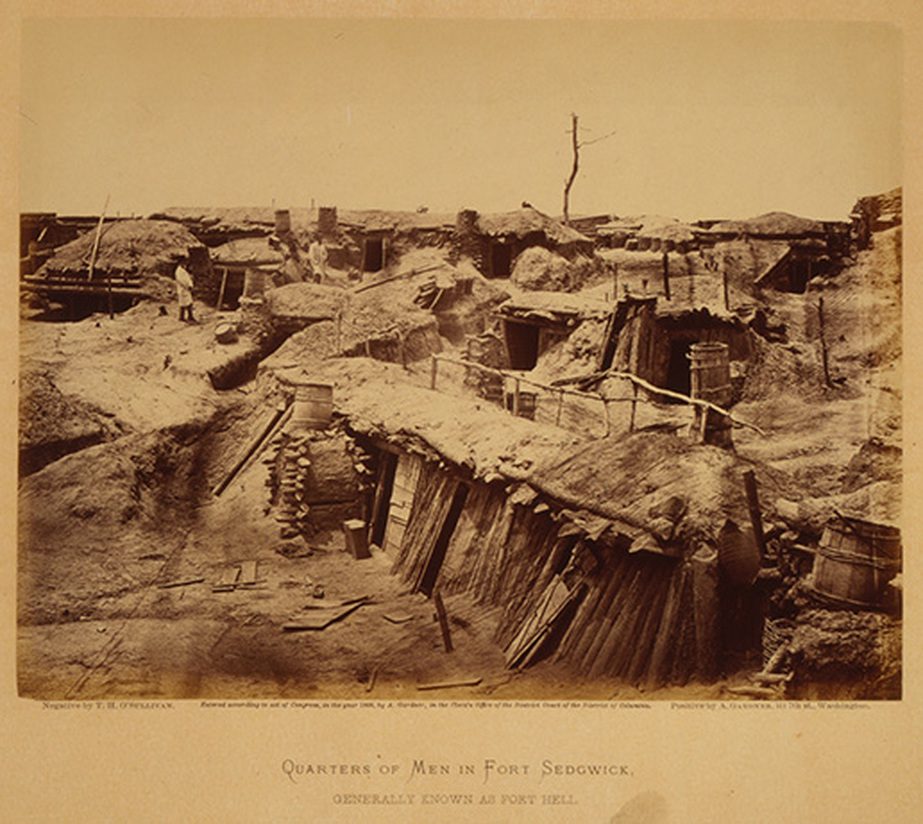

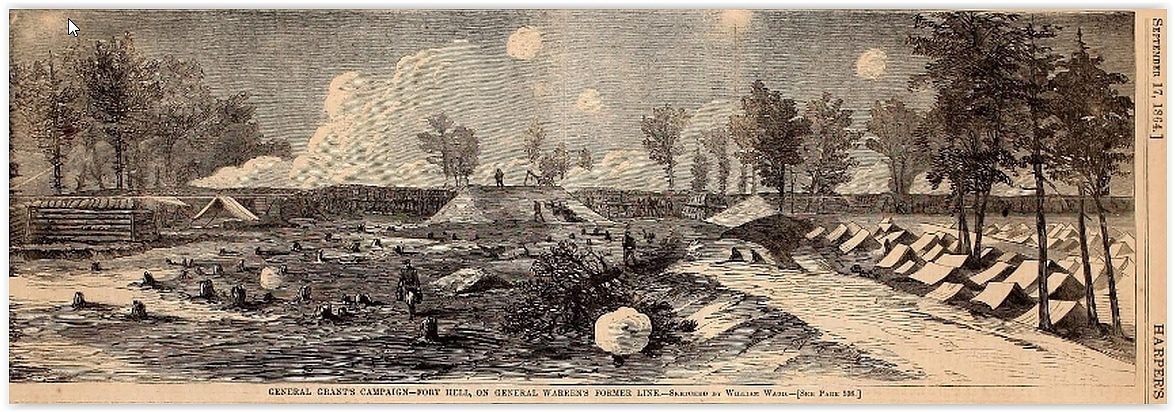

This bolt was recovered in the late 1960s era at the site of Ft. Sedgewick, called by the Confederates Ft. Hell. Fort Sedgewick or “Fort Hell” was one of the larger forts of the Union Army during the Civil War with a garrison of 800 men and 17 cannon. The fort occupied the most elevated natural position giving Union troops an unlimited view of their enemy and of Petersburg, Virginia. The fort earned its nickname from the Confederate troops because of the constant, intense artillery fire from the cannons. The last attack launched from Fort Hell was April 2, 1865, when Union soldiers attacked Confederate lines with a “blistering 30-minute bombardment.” Despite the repeated bloody attacks by Union troops from Fort Hell, Confederate soldiers held their lines long enough to enable General Robert E. Lee and his men to escape—to Appomattox where Lee ended up surrendering on April 9, 1865.

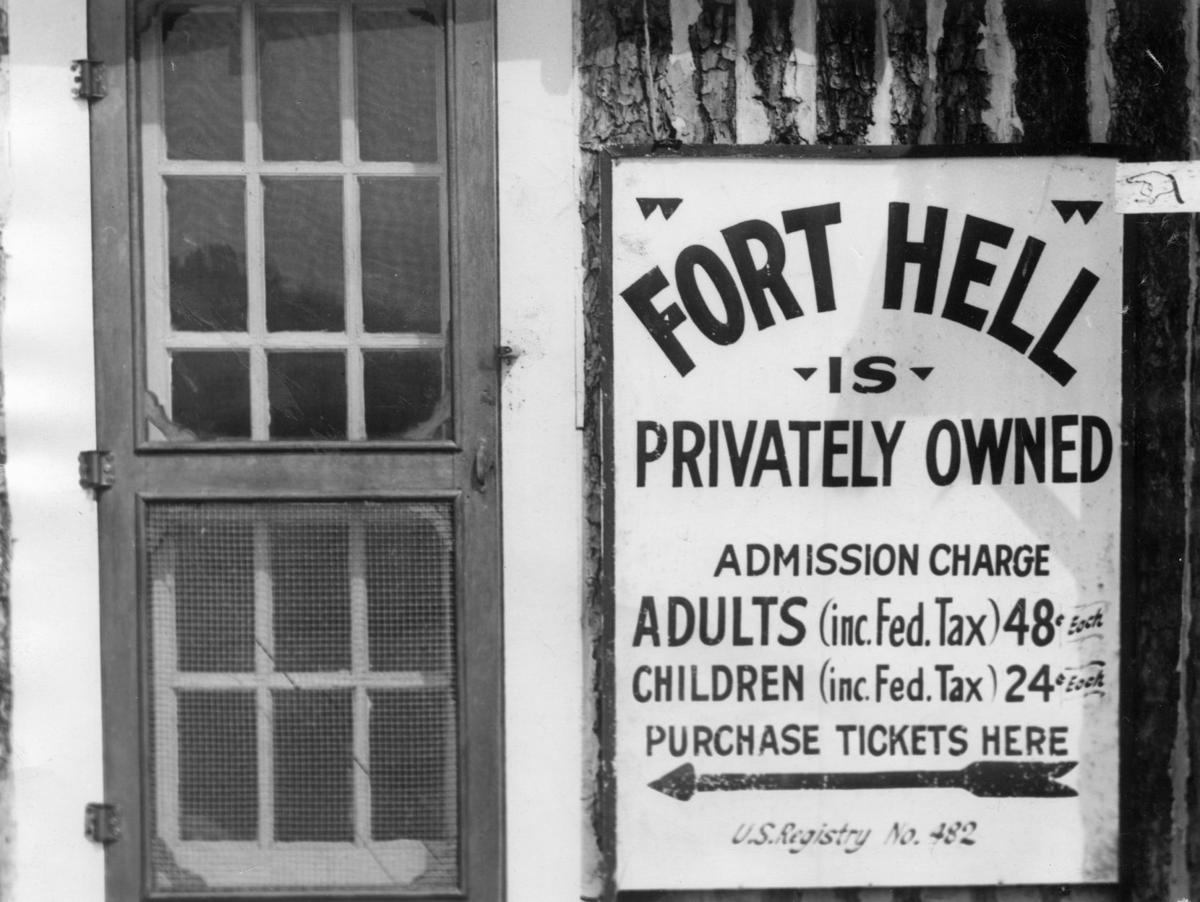

In the decades following the Civil War, the battleground was preserved and even housed a museum that attracted thousands of visitors. However, in 1966 it was announced that the land would be sold and the old trenches and the museum would be leveled. In 1966, David A. Lyon, a spokesperson for the Lyon family who had owned the property for over 30 years, said the decision to sell the property was due to the fact that business had declined by about one-third.

While the historic fortification withstood endless days of pounding from enemy cannons, its ultimate downfall was by the bulldozer.